Confidence and Nationalism rising in Modi’s 'New India'

Source : Stimson

|

| Representative Image |

A new survey in India examines public opinion on domestic politics and national security issues to understand the political incentives leaders face during interstate crises in Southern Asia. This survey reveals how public attitudes could shape Indian diplomacy, crisis escalation, and nuclear force development. The nature of popular views on these topics and their effects on elite decision-making are understudied. Understanding those incentives would help the United States and other diplomatic partners of India clarify mutual expectations and promote regional stability.

Please

join us for a discussion with the authors of this recent groundbreaking

publication, here.

A new

7000-person survey conducted by phone in India between April 13 and May 14,

2022, finds:

- high levels of support for

Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who likely remains among the most popular

national leaders in the world today;

- extraordinary nationalist

sentiment among Indians, at high levels compared to prior cross-national

surveys using identical question wording;

- troubling signs of intolerance

toward India’s large Muslim minority, which helps provide context to recent

controversies;

- strong confidence in the Indian

government’s ability to defend India against potential domestic and

foreign threats;

- expectations among a majority

of Indian respondents that the U.S. military would support India in the

event of a war with China or Pakistan; and

- large majorities in favor of

Indian numerical nuclear superiority against its adversaries.

The survey

was intended to measure Indian attitudes towards the current government,

India’s domestic challenges, and inter-state disputes as part of a broader

Stimson Center initiative to understand the political incentives leaders face

during interstate crises in southern Asia.1 This nationally representative

survey was translated and fielded in 12 languages for respondents in all 28 Indian

states and 6 of India’s 8 union territories by the Centre for Voting Opinion

& Trends in Election Research (CVoter).2 CVoter is a widely used

public opinion firm that regularly partners with Indian newspapers, magazines,

television news channels, as well as academic researchers.3 This project

note outlines the key descriptive findings from the survey.4

Political Support and Partisan Leanings

Prime

Minister Modi received support from a large majority in our survey, with 71%

either somewhat or strongly supporting him.5 This confirms a notable

positive shift from last year when Modi’s approval levels were dampened by the

COVID-19 crisis and challenged later in 2021 due to his government’s

controversial farm laws.6 Support for his party, the Bharatiya Janata

Party (BJP), was also high at 61%. Hindu respondents were significantly more

likely to support Modi and the BJP relative to non-Hindu respondents in the

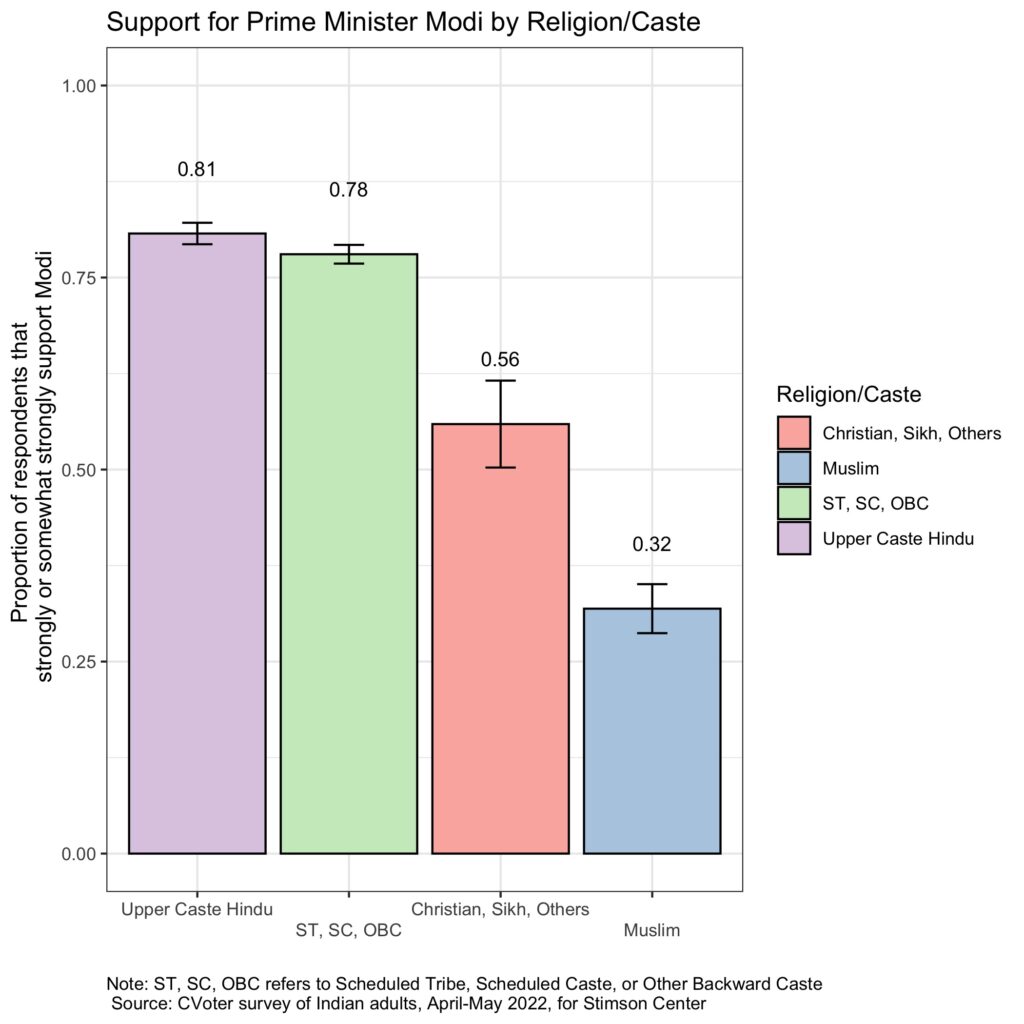

sample (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

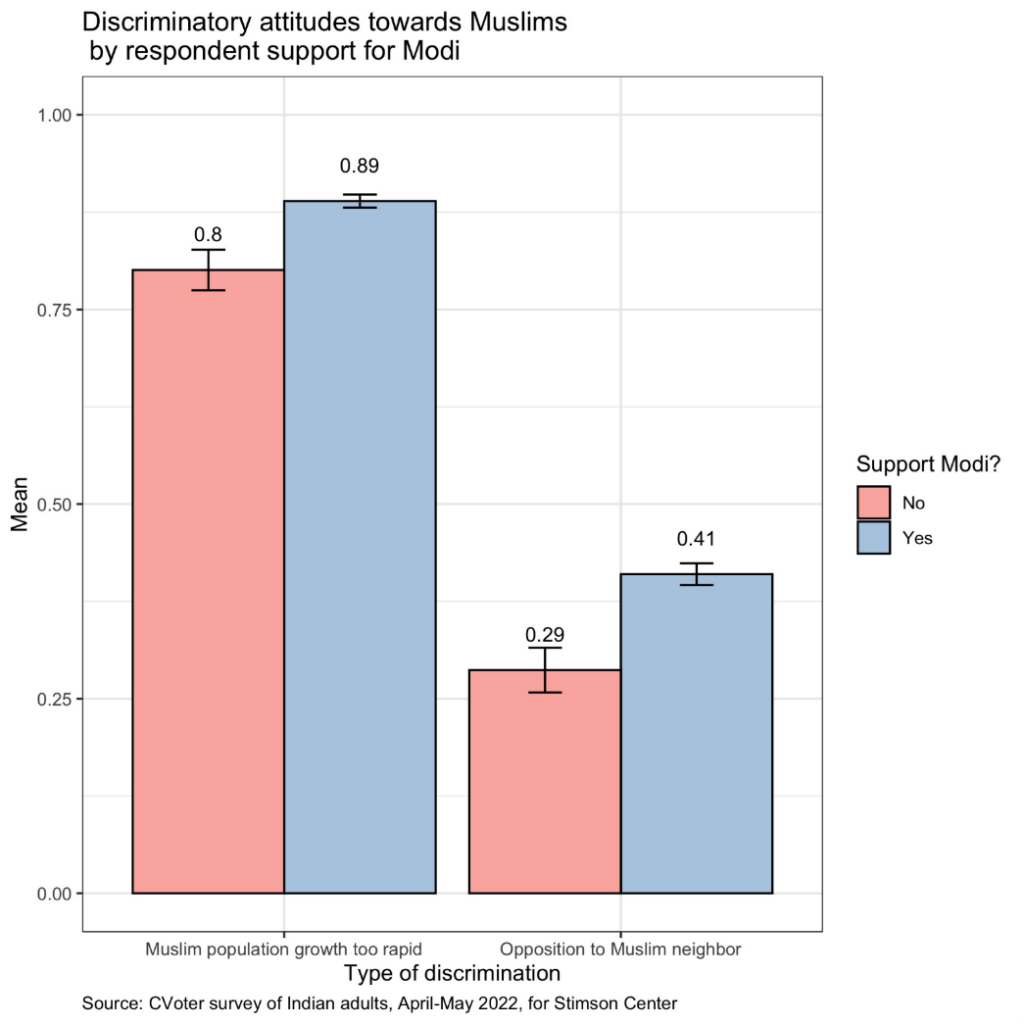

Worryingly,

supporters of Modi or the BJP were more likely to express discriminatory

attitudes toward Muslims, such as stating they did not want to have a Muslim as

a neighbor or that they believed India’s Muslim population was growing too

fast.7 It is worth stating, however, that among all non-Muslim

respondents, including both Modi supporters and skeptics, such discriminatory

attitudes were widespread. An overwhelming majority of 78 percent of

respondents stated that they believed India’s Muslim population was growing too

fast. Such attitudes may explain why the historically secular Indian National

Congress has publicly sought to disassociate itself from any “branding… as a

Muslim party”8 and why other parties with nationwide aspirations, such as

the Aam Aadmi Party, have also been accused of embracing a softer version of

Hindu nationalist politics.9 Such anti-Muslim sentiments could generate

meaningful international repercussions if they influence national policy or

political statements, a tendency which may be reflected in recent

controversies. For example, India received considerable criticism from Muslim-majority

countries following derogatory statements about the Prophet Mohammad made by

BJP spokespersons.10 The U.S. government too has expressed concern about

restrictions against and violence targeted at Indian religious minorities.11

Figure 2.

Nationalism

Respondents were overwhelmingly nationalistic in their responses. 90% strongly or somewhat agreed with the statement that “India is a better country than most other countries.” This number, large in absolute terms, is also large when compared to other contexts.12 U.S. citizens, for example, are typically viewed as more nationalist than average, but in 2014 only 70 percent of respondents strongly or somewhat agreed that the U.S. is a better country than most.13 While American exceptionalism is a well-understood domain of study, self-perceptions of Indian exceptionalism are relatively underexplored.

Nationalist

sentiment dovetailed with negative opinions of neighboring countries. When

asked about Pakistan, 67% of respondents expressed their “dislike to a great

extent” and a nearly equivalent 65% “disliked” China to “a great extent.” These

views covaried in intuitive ways, such that respondents with greater levels of

baseline support for Modi were more likely to hold negative opinions of

Pakistan and China, and more nationalistic individuals were also more likely to

believe India could defeat China and Pakistan militarily.

A majority of

respondents said that the United States would “definitely” or “probably” help

in the event of an Indian war with China (56 percent) or Pakistan (59

percent).

Respondents

in India’s south tended to have somewhat more favorable—though still

overwhelmingly negative—views of China, but this north-south distinction was

less evident in attitudes toward Pakistan. We find little evidence that

unfavorable opinions toward China or Pakistan vary substantively by respondent

age.

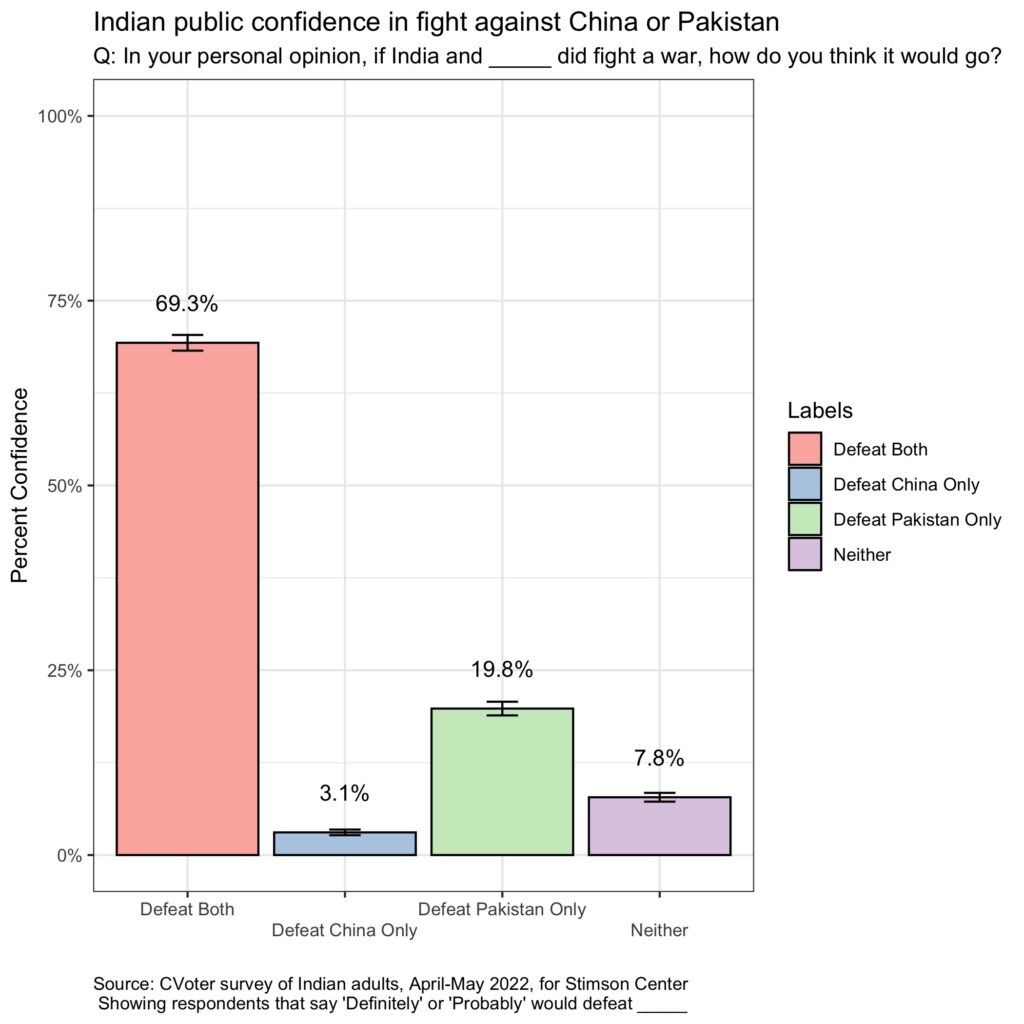

Figure 3.

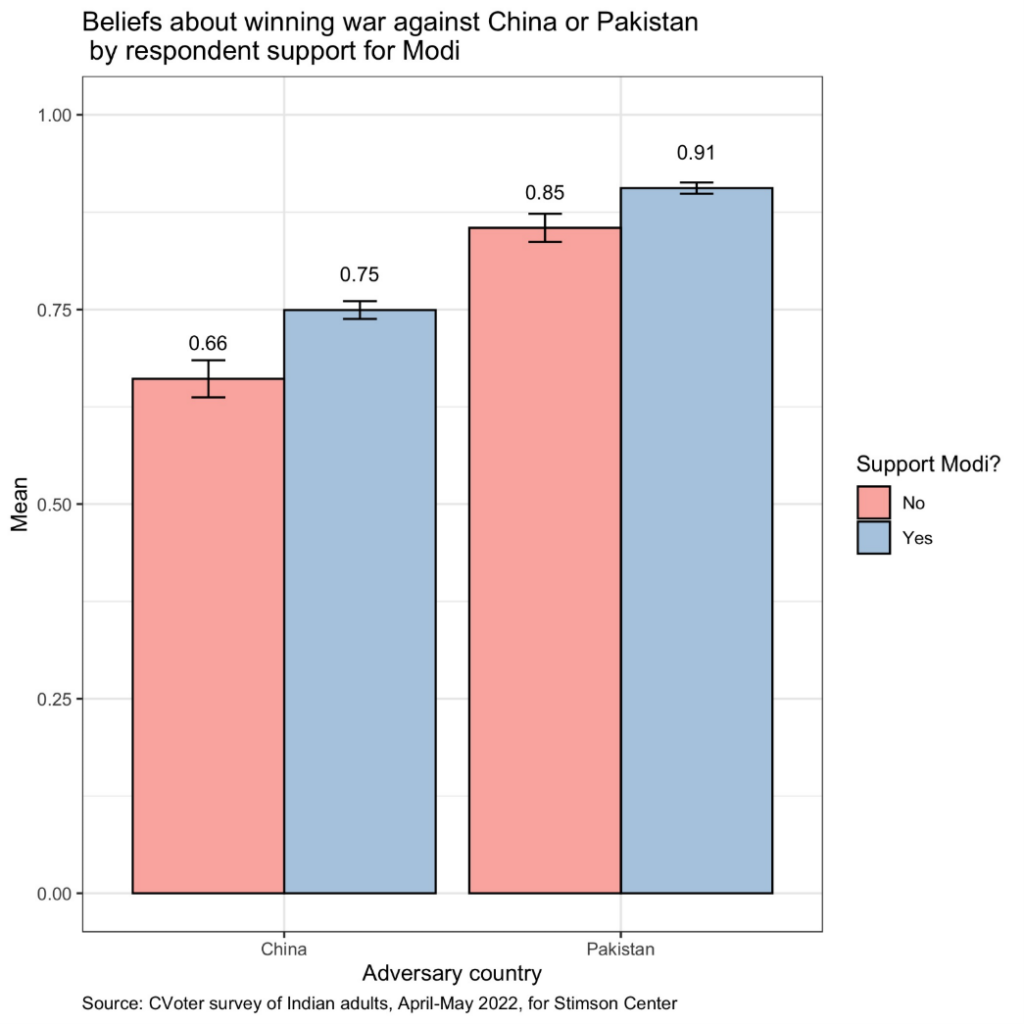

Nationalist sentiment also manifested as confidence in India’s military prowess and state strength. 90% of respondents said that India would probably or definitely defeat Pakistan in case of a war between the two hostile neighbors. A smaller, but still sizeable, percentage (72%) believed that India would probably or definitely defeat China in the event of a war. This may mirror confident public statements by Indian military officials,14 but deviates from some expert analysis which suggests that India is likely at a disadvantage in a military contest with China.15 Modi supporters were modestly more likely to assess that India could defeat China or Pakistan than non-supporters.

Figure 4

Views of Indian Conflict Scenarios and Nuclear Weapons Needs

Respondents

were divided about whether other countries would come to India’s defense in the

event of an international conflict. A majority of respondents said that the

United States would “definitely” or “probably” help in the event of an Indian

war with China (56 percent) or Pakistan (59 percent), with a remaining large

minority skeptical of U.S. aid in such scenarios. In contrast, surveys of U.S.

respondents have found sizeable majorities might prefer to avoid entanglement

in a Sino-Indian military conflict.16 For their part, Indian military

leaders and strategists have stressed that India will have to fight its own wars

alone without counting on others.17

A similar

majority of Indian respondents assessed China would come to Pakistan’s aid in

the event of an Indo-Pakistani war (56 percent) and that Pakistan would come to

China’s aid in the event of a Sino-Indian war (59 percent) consistent with

Indian strategists’ fears of a “two-front war.” Combining these results shows

that a large minority of respondents, roughly 4 in 10, foresee a scenario where

India might have to fight both China and Pakistan simultaneously without U.S.

help.

An overwhelming majority

of respondents—68 percent—assessed India needed more nuclear weapons than its

enemies.

We also asked about respondent views on the number of nuclear weapons India needs. An overwhelming majority—68 percent—assessed India needed more than its enemies. Just 13 percent said India should have about as many nuclear weapons as its enemies, and only a handful assessed that India should only have “a few” or “not any” nuclear weapons. These public preferences may be incompatible with India’s current nuclear force structure where most non-governmental organizations assess that China has more operational nuclear weapons than India while Pakistan has the same or slightly more nuclear weapons than India. 18 If these preferences hold, they could serve as a political driver for an arms race with China, which U.S. assessments forecast could quadruple its nuclear forces to 1,000 weapons by 2030.19

Implications

The nature

of Indian public opinion on national security issues and the effect of mass

views on elite decision-making—which together determine the foreign policy

“accountability environment”—remains remarkably understudied.20 Yet our

survey identifies several areas where public views may shape Indian government

preferences in ways that will be important for India’s diplomatic partners to

understand. Several implications appear most prominent from our

analysis.

- No signs of erosion of Modi’s

domestic political support: Our findings reaffirm other polls that show Modi

is one of the most popular leaders—and perhaps the most popular

leader—of any democratic country.21 This is true despite seeming

missteps his government made in the face of the pandemic and associated

economic travails.

- India’s extraordinary nationalism may

prove challenging for Indian diplomatic partners to navigate: Status concerns are common in

global politics, but the Indian polity appears to hold broadly a belief

that India is better than most other countries. India’s Minister of

External Affairs has popularized the idea that India will go “the India

way.”22 Our findings indicate Indian citizens may perceive few

reasons to compromise on issues like relations with Russia or its domestic

institutions given India’s position in world politics.

- Widespread support for anti-Muslim

attitudes may create domestic political incentives for anti-Muslim

policies: Modi’s

government has faced sustained allegations of anti-Muslim animus. Our

survey results suggest that popular attitudes toward Muslims may encourage

rather than halt any anti-Muslim impulses of the BJP-led government. Such

sentiment could stoke friction between New Delhi and its neighbors and

regional partners, a danger highlighted following recent anti-Muslim

remarks expressed by members of the ruling party.23

- Indian self-confidence may lead to

mistaken popular views of Indian military prowess: India has considerable military

capabilities against its most likely regional opponents.24 Yet Indian

confidence that India would likely defeat China or Pakistan may exceed what

a careful net assessment might warrant. This in turn might make it

challenging for Indian leaders to back down in crises, since their publics

may view such conflicts as winnable even if the military balance is not in

their favor.25

- U.S. officials may seek to signal

their willingness to aid India in the event of conflict with China to

correct widespread popular doubts: A majority of Indians believe the U.S. would

assist it in the event of a conflict with China or Pakistan. The United

States likely could do more to publicly signal its reliability regarding a

China contingency. The United States offered considerable material support

to India in past crises with China (in 1962 and 2020) but both times

cloaked some of that assistance in secrecy based on the requests of New

Delhi.26 At the same time, U.S. officials likely do not foresee

significant material support in the event of an India-Pakistan conflict

and instead seek to retain a viable third-party crisis management role.

U.S. officials should be aware that they may struggle to fulfill Indian

public expectations in such circumstances.

- Public opinion may encourage rather

than restrain any contemplated future Indian nuclear force buildup. Our poll finds an Indian

public that prefers Indian numerical nuclear superiority against its

adversaries by large margins. It is consistent with earlier public opinion

research that suggested that the Indian public was comfortable with

nuclear weapons as tools of statecraft in specific, plausible scenarios.27 Such

views help provide context to Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s decision to

emphasize on the campaign trail in 2019 that Indian nuclear weapons were

not kept as mere showpieces.28 Based on limited inquiries to date,

further research is needed to untangle public understanding of nuclear

weapons and their salience in contemporary debates.

No comments: